A helpful blog written by a colleague a few years ago, titled The Clog Blog explores what happens when backpressure suddenly spikes in an LC system due to a blockage. In short, clogs typically occur when particulates enter the flow path and reach the column inlet frit. If these particles are larger than the frit pores, they become trapped at the column head, restricting flow. As a result, the mobile phase encounters resistance and the system backpressure increases as the pump continues to push solvent through the obstructed pathway.

There are three main origins of particulates that can be introduced into the system:

- Sample

- Mobile Phase

- LC instrument wear and tear

1. The Sample: The sample itself is often the most common source of particulate contamination. When working with complex samples, it is essential to perform proper sample cleanup, either by centrifugation or filtration, prior to analysis. If filtration is chosen, selecting an appropriate filter pore size is important and should be based on the column’s particle type and size. For columns packed with fully porous particles, such as those used in Restek’s Force or Ultra columns, there is a wider distribution in particle size compared to superficially porous particles. To prevent particle loss during packing and use, these columns are manufactured with frits that are smaller than the average particle size. In contrast, superficially porous particles, such as those used in Restek’s Raptor columns, are engineered to be monodisperse, meaning they are uniform in size. This allows the use of frits with pore sizes that are much closer in size to the particles themselves, minimizing potential clogging issues while still retaining the packing material. Particles in the tens of micrometers are not visible to the naked eye and visual inspection alone to judge sample cleanliness can be highly misleading. Proper sample preparation is essential, as it helps prevent clogs, reduces troubleshooting time, and ultimately saves money over the course of an analysis. To assist in selecting the appropriate filter size for your analysis, Table 1 below summarizes typical column particle sizes, corresponding frit sizes, and the recommended minimum filtration pore size.

| Analytical Column Particle Size | Typical Frit Size | Minimal Filtration Size |

| 5 µm | 2 µm | 0.45 µm |

| 3 µm | 0.5 µm | 0.2 µm |

| 2.7 µm (Raptor) | 2 µm | *0.45 µm |

| 1.8 µm | 0.5 µm | 0.2 µm |

Table 1: Column particle size, typical frit size, and minimal filtration size chart.

*While the minimal filtration size largely considers the porosity of the column frits, the particle size also needs to be considered. For example, the interstitial channels of Raptor 2.7 µm particles are ~0.6 µm so filtration under 0.45 µm should be considered to maximize column lifetimes.

2. The Mobile Phase: Mobile phase is another common source of contamination and clogging in LC systems. This often occurs when bacterial growth develops in poorly maintained aqueous mobile phases. The issue tends to arise more quickly in warmer environments where bacteria thrive, so if you are in a region with a warmer climate, more frequent monitoring and maintenance may be necessary. Regularly changing mobile phases is an effective way to minimize the risk of clogging caused by microbial contamination. The types of bacteria that grow in these conditions are typically waterborne and flourish in moist environments. A common example is Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a rod-shaped bacterium that ranges from approximately 1.5- 5 µm in length and 0.5- 1 µm in width. Although invisible to the naked eye, these microorganisms can still become trapped in the column frit and cause clogs, making visual inspection of mobile phases an unreliable method for assessing cleanliness. To help prevent these issues, it is best practice to always use freshly prepared mobile phases.

Buffer salts, commonly used as mobile phase additives in liquid chromatography, also pose a risk of clogging when precipitation occurs. The most frequent cause of salt precipitation is the mixing of buffer salts with high concentrations of organic solvents such as acetonitrile, which many salts have very limited solubility.

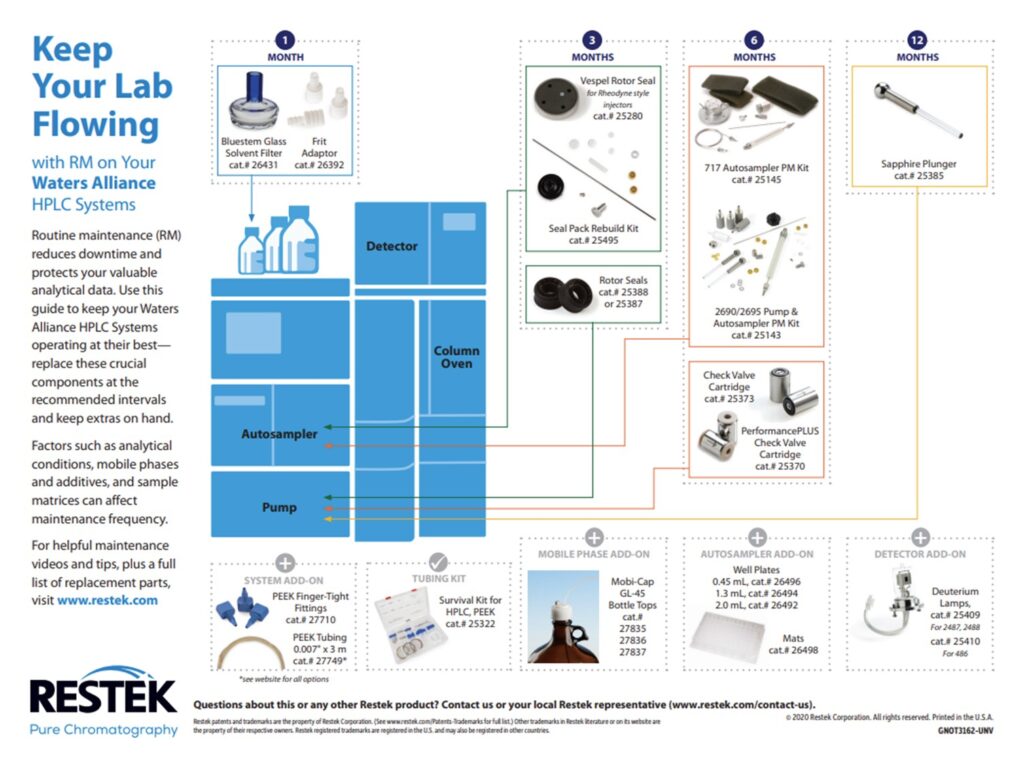

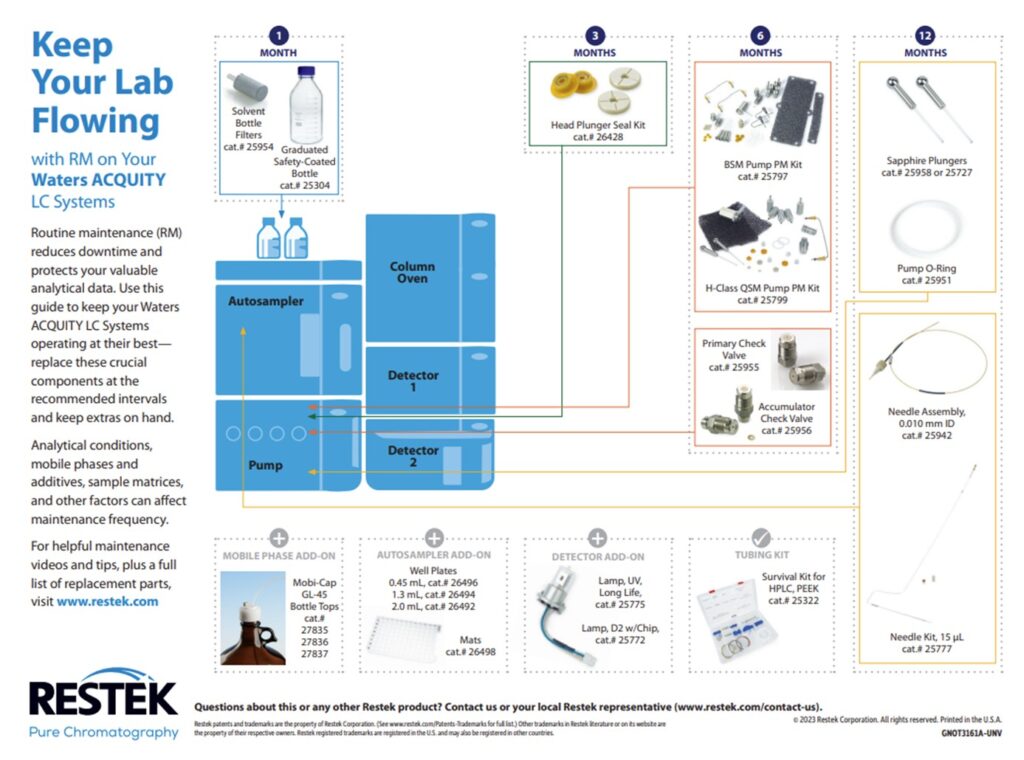

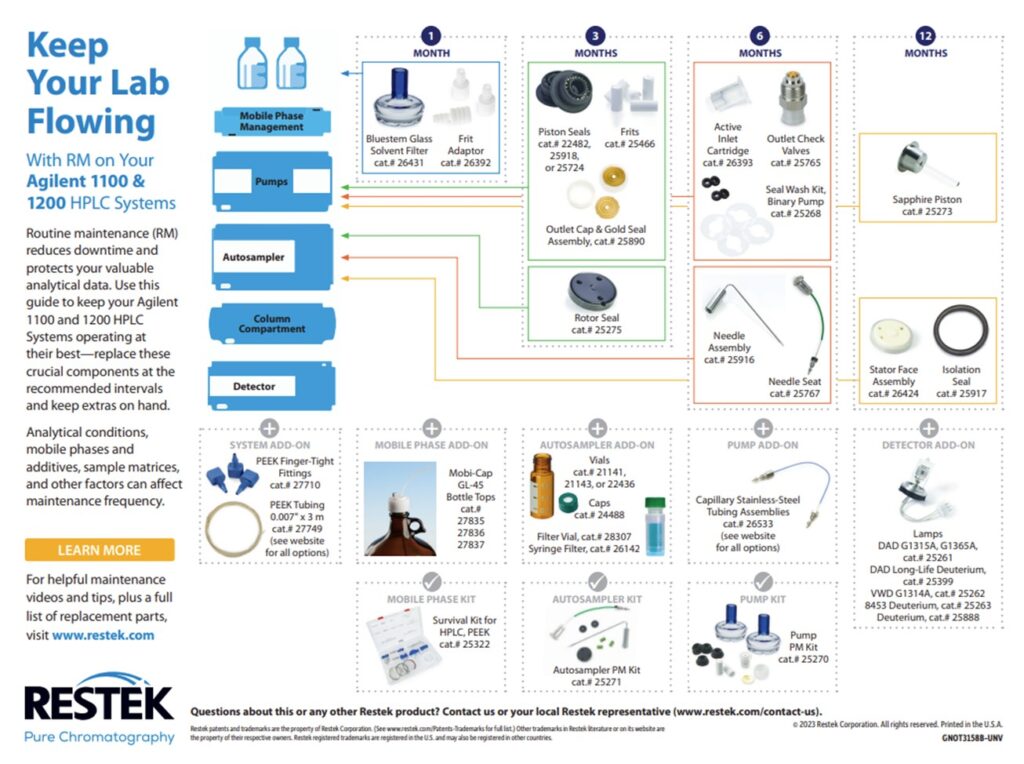

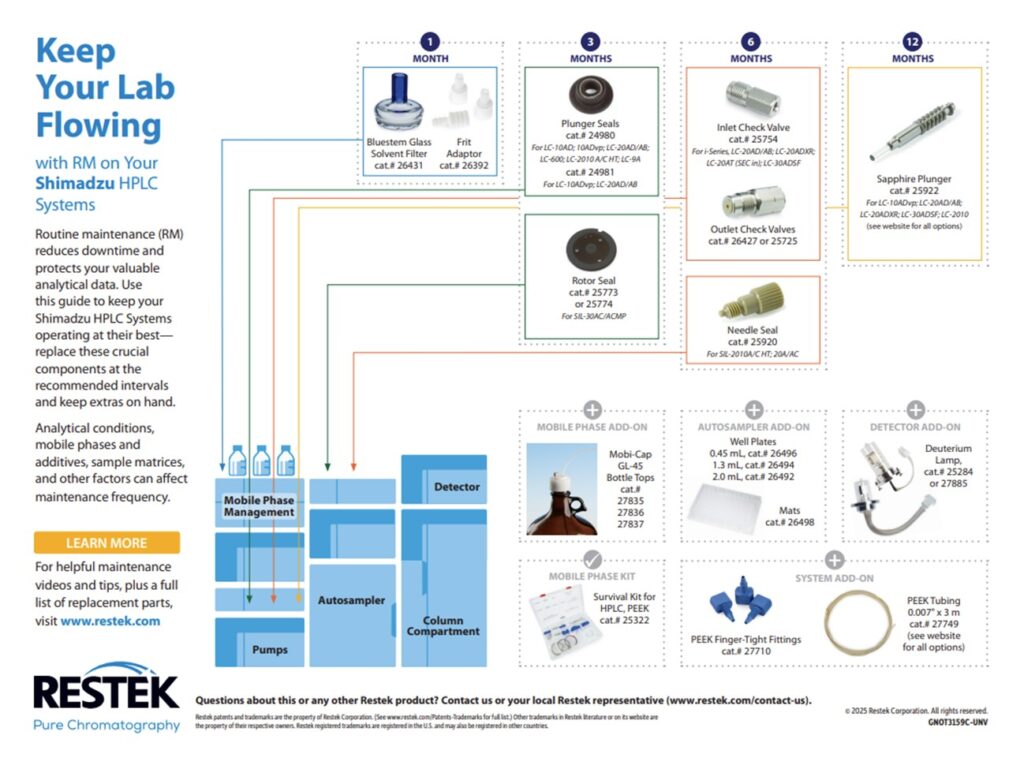

3. LC Instrument Wear and Tear: There are several consumable parts in the flow path that should be changed during regular maintenance. If these parts are not changed regularly, they can start to wear out and potentially shed particles. Any particles that are introduced into the flow path can cause clogs in the column, lines, and/or the injector. The best practice to avoid clogs due to consumable wear and tear is to change the consumables regularly on a preventative maintenance schedule. Each instrument manufacturer has guidelines for when to perform routine maintenance and the charts below have been compiled for Waters Alliance, Waters Acquity, Agilent 1100 & 1200 and Shimadzu HPLC systems.

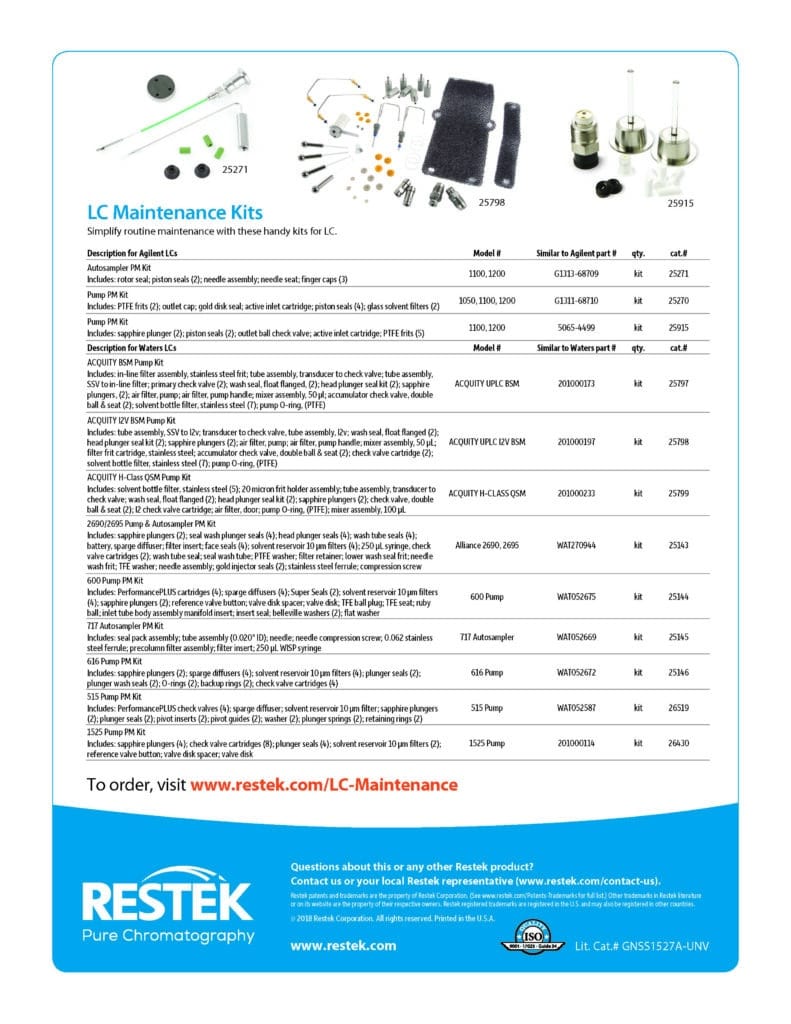

Restek also offers routine LC maintenance kits for Agilent and Waters systems:

In summary, LC system clogs are typically caused by particulates introduced from the sample, mobile phase, or instrument consumables. To minimize the risk of blockages, always filter/centrifuge samples, use freshly prepared mobile phases, and perform routine preventative maintenance.