Introduction

Plastic production began a little over a century ago with the synthesis of Bakelite in 1909, a material derived from phenols and formaldehyde. Today, most plastics are produced from fossil hydrocarbons (petroleum-based), with global production and demand, including elastomers and fibers, reaching about 400 million metric tons in 2019, and experiencing annual growth rate of 3.6% since 2000 [9]. Since industrial-scale production began in the 1950s, roughly 80% of the 8 billion metric tons of plastic ever manufactured have accumulated in landfills or the environment [10], where they persist due to their resistance to degradation.

Plastics fall into two primary categories based on their thermal behavior: thermosets and thermoplastics. Thermosets form permanent, cross-linked networks during curing and cannot be remelted. In contrast, thermoplastics like polyethylene (PE); polypropylene (PP); polyvinyl chloride (PVC); polyethylene terephthalate (PET); and polystyrene (PS) consist of linear polymer chains that can be reshaped upon heating, theoretically enabling recycling—though less than 10% of plastics are effectively recycled [4]. Polyethylene, the most prevalent environmental pollutant among polymers, is followed by PP and PS [5]. Beyond these, plastics like poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA); polyamide (PA); and polyurethane (PUR) are widely used alongside bioplastics, which are touted as sustainable alternatives but often require specific conditions to degrade and may still pose ecological risks.

Most traditional plastics are not biodegradable; as a result, they accumulate rather than decompose. With the vast and increasing amount of plastic waste disposed of in the environment, there is growing concern that plastic pollution can potentially cause both physical and chemical harm to wildlife and humans through direct ingestion and sorption and serve as a means of transferring other environmental contaminants.

Although it is difficult to biodegrade, the degradation, disintegration, and fragmentation of plastic waste in the environment leads to the formation of smaller sizes and particles. These fragments are commonly referred to as microplastics and nanoplastics, which are more challenging to separate from environmental samples. They evade wastewater treatment systems, entering oceans, freshwater supplies, and even the air. Recent studies detect microplastics in 80% of bottled water and tap water samples evaluated in different studies. Airborne microplastics, including those from tire wear and synthetic textiles, are now detected in remote regions like the Arctic and human lung tissue, raising concerns about inhalation risks.

The rising concern about microplastic and nanoplastic pollution has also led to an increased motivation to substitute petrochemical-based plastics with environmentally friendly biobased and biodegradable alternatives. Biobased plastics are entirely or partly derived from biomass (including plant, animal, and marine or forestry materials) but are not necessarily biodegradable. They are used widely in clothing and wet wipes and can accumulate in soils through the application of solid biosolid fertilizers. The ecotoxicity of these biobased fibers is only partially understood, with Courtene-Jones et al.[2] highlighting the greater acute toxicity at high concentration for the biobased fibers and broadly sublethal effects compared to polyester. A call for detailed testing of these plastic alternatives prior to advocating for their use is of utmost importance.

Size Categorization of Plastics

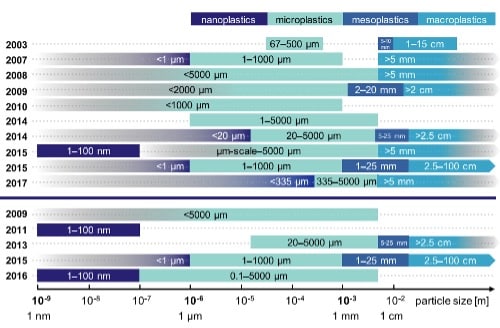

Plastics disintegrate into progressively smaller fragments, classified microplastics (MP), or even smaller pieces known as nanoplastics (NP), although standardized definitions remain debated. Currently, microplastics are widely defined as being greater than 100 nm and less than 5 mm in diameter, while nanoplastics span 1 to 100 nm—dimensions comparable to engineered nanoparticles. Larger plastic debris is categorized hierarchically: mesoplastics (5–10 mm); macroplastics (10 mm–15 cm); and megaplastics (>15 cm), though terminology varies across studies (Figure 1).

Micro- and nanoplastics originate from primary and secondary sources. Primary sources are those that deliberately create micro- and nanoplastics for consumer and industrial uses, such as microbeads in cosmetics (banned in several countries but still prevalent in some personal care products); pellets for industrial abrasives; and nanocarriers in drug delivery systems. Secondary sources of micro- and nanoplastics result from the fragmentation of larger plastic waste through UV photodegradation; mechanical abrasion (e.g., tire wear, laundry cycles); and environmental weathering. Notably, it is estimated that secondary sources of microplastics currently account for the dominance of microplastics in the environment [1].

Nanoplastics, due to their colloidal size, exhibit unique behaviors: higher surface-area-to-volume ratios enhance adsorption of pollutants (e.g., POPs, heavy metals), and their ability to cross biological barriers (e.g., intestinal epithelium, blood-brain barrier) raise concerns about bioaccumulation. Recent studies detect nanoplastics in human blood, placental tissue, and marine organisms, though analytical challenges persist in quantifying their environmental prevalence.

Detection and Analysis of Microplastics and Nanoplastics

The analysis of micro- and nanoplastics presents formidable challenges due to their heterogeneity in size, polymer composition, morphology, and environmental interactions. These particles span a broad size range (1 nm to 5 mm); encompass diverse polymer types (e.g., PE, PP, PS, PET, and biopolymers); and exhibit varied shapes (fibers, fragments, films, foams). Further complexity arises from additives (e.g., phthalates, brominated flame retardants); weathering byproducts; and sorbed contaminants, including persistent organic pollutants (POPs) like polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs); polycyclic aromatic compounds (PACs); dioxin-like chemicals (PCDDs/PCDFs); and polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) as well as heavy metals and pharmaceuticals. Their surface properties (hydrophobicity, charge) and aging states further complicate detection, especially in complex matrices like biological tissues or wastewater.

Current isolation methods rely on density separation and size filtration, but these fail to capture nanoplastics or microplastics in aggregated forms. In wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), the concentration of microplastics after primary treatments is reduced by up to 70%, whereas it can be further reduced by 80–90% and 99% in the secondary and tertiary effluents [7, 13], yet effluent still releases 10⁵–10⁸ particles daily per plant [12]. For biological tissues, acid/alkali digestion or enzymatic degradation is used to dissolve organic matter, though this procedure risks polymer degradation. Terrestrial organisms remain understudied, with limited protocols for soil or plant matrices.

Human exposure is significant: MPs are ingested via seafood, bottled water, and even airborne dust, with estimates suggesting 39,000–52,000 particles annually from different food groups intake, which together accounted for 15% of the daily average caloric intake consumed by adults in the U.S. [3]. Nanoplastics penetrate placental barriers, brain barriers, bone marrow, and vascular systems as evidenced by their detection in human blood, placentas, spleen, lung, semen, and feaces samples [11].

Analytical Techniques for Characterization

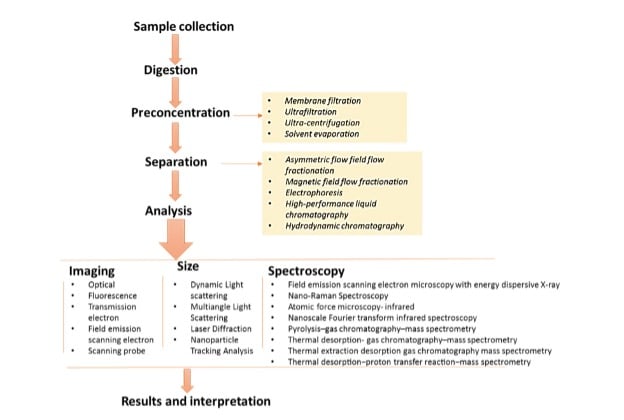

Typically, visual characterization techniques have been used to reduce the number of particles that are later chemically characterized. Different methods have been adopted to confirm the composition of micro- and nanoplastics, enabling the identification, characterization, and quantification of these materials in sample matrices. These methods include Vibration Spectroscopy and Mass Spectroscopy. Enyoh et al. [6] provided a detailed description of new analytical approaches for effective quantification and identification of micro- and nanoplastics in environmental samples (Figure 2).

Vibration Spectroscopy, such as Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) and Raman Microscopy, provides polymer identification and particle imaging. This spectroscopy technique provides both visual information and the composition of plastic particles when combined with optical microscopy. Raman spectroscopy has a better size resolution as it can detect particles down to a size of 1 μm while FTIR has a less precise size resolution and detects particles down to a size of 10–20 μm. The limitation of this method is that the signal obtained is highly dependent on the size of the particle analyzed, and typically, a well-separated sample is required.

Mass spectroscopy-based methods, such as gas chromatography coupled with thermal desorption (TDS-GC-MS) and pyrolysis (py-GC-MS), have increased sensitivity, which also allows detection of nanoplastics in sample matrices. These techniques are suitable for identifying and quantifying a mixture of plastic polymers in environmental matrices and are unaffected by size limitations, offering strong resistance to interference.

Thermal desorption (TDS) is a method in which materials are heated to release adsorbed chemicals as volatile molecules while pyrolysis-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry is a technique for chemical analysis in which a sample is heated to break down, resulting in the formation of smaller molecules that are separated and identified using gas chromatography and mass spectrometry. TD-GC/MS can be combined with Pyr-GC/MS and used for nanoplastics analysis. In this method, adsorbed chemicals are first desorbed from the particle by TD, and then the polymer is broken by pyrolysis. Both particle treatment methods are connected directly to the same GC-MS equipment, which analyzes desorbed molecules and pyrolysis products.

The coupling of two-dimensional gas chromatography with time-of-flight mass spectrometry (GCxGC-TOFMS) has been adopted for the better identification and quantification of chemicals that are associated with microplastics and nanoplastics. The approach requires minimal sample preparation and provides powerful chromatographic separation with high-quality deconvoluted mass spectral data, allowing for the resolution, detection, identification, and quantification of microplastics and nanoplastics degradation products, additives, and other complex mixtures of chemicals found in the environment. Compared to optical spectrum techniques, pyrolysis gas chromatography has revolutionized our ability to identify micro- and nanoplastic types and quantify their presence in biological tissue and environmental samples.

The technique has demonstrated remarkable advantages in the micro- and nanoplastics screening phase, particularly in the detection of low-concentration and small-sized micro- and nanoplastics as well as in the analysis of complex sample matrices.

The harmonization, validation, and standardization of methods for analysis, their comparison, harmonization, and standardization are inevitable to ensure reliable results on the contamination of micro- and nanoplastics in different media. For this purpose, suitable reference materials are needed. However, reference materials that resemble the particles found in real samples (including a variety of polymer types, a broad size range, different shapes, and various aging states) are still lacking.

Restek is advancing its research into microplastics and nanoplastics with cutting-edge analytical capabilities. Our newly acquired Benchtop LECO Pegasus BTX 4D system (LECO Corporation, St. Joseph, U.S.A.), equipped with a thermal modulator and interfaced with an OPTIC-4 injector (GL Sciences BV), has exceptional detectability and sensitivity and empowers precise identification and analysis of these contaminants in environmental samples. This innovative instrumentation positions Restek at the forefront of environmental polymer research, delivering reliable data to address global microplastic pollution challenges.

References:

- L. An, Q. Liu, Y. Deng, W. Wu, Y. Gao, W. Ling, Sources of microplastic in the environment. In Microplastics in terrestrial environments: Emerging contaminants and major challenges, Springer Cham, 2020, 143-159.

- W. Courtene-Jones, F. De Falco, F. Burgevin, R.D. Handy, R.C. Thompson, Are biobased microfibers less harmful than conventional plastic microfibers: evidence from earthworms. Environ. Sci. Technol., 58 (46) (2024) 20366-20377. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.4c05856

- K.D. Cox, G.A. Covernton, H.L. Davies, J.F. Dower, F. Juanes, S.E. Dudas, Human consumption of microplastics, Environ. Sci. Technol., 53 (12) (2019) 7068-7074. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b01517

- W. d’Ambrières, Plastics recycling worldwide: current overview and desirable changes. Field Actions Science Reports, J. Field Actions, (Special Issue 19)(2019) 12-21. https://journals.openedition.org/factsreports/5102

- J. Delgado-Gallardo, G.L. Sullivan, P. Esteban, Z. Wang, O. Arar, Z. Li, T.M. Watson, S. Sarp, From sampling to analysis: A critical review of techniques used in the detection of micro-and nanoplastics in aquatic environments, Acs ES&T Water, 1 (4) (2021) 748-764. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsestwater.0c00228

- C.E. Enyoh, Q. Wang, T. Chowdhury, W. Wang, S. Lu, K. Xiao, M.A.H. Chowdhury, New analytical approaches for effective quantification and identification of nanoplastics in environmental samples. Processes, 9 (11) (2021) 2086. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr9112086

- E.A. Gies, J.L. LeNoble, M. Noël, A. Etemadifar, F. Bishay, E.R. Hall, P.S. Ross, Retention of microplastics in a major secondary wastewater treatment plant in Vancouver, Canada. Mar. Pollut. Bull., 133 (2018) 553-561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.06.006

- N.B. Hartmann, T. Huffer, R.C. Thompson, M. Hassellov, A. Verschoor, A.E. Daugaard, S. Rist, T. Karlsson, N. Brennholt, M. Cole, M.P. Herrling, Are we speaking the same language? Recommendations for a definition and categorization framework for plastic debris, Environ. Sci. Technol., 53 (3) 2019. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b05297

- N. Karali, N. Khanna, N. Shah, Climate impact of primary plastic production, OSTI.GOV, 2024, Accessed May 2025. https://doi.org/10.2172/2336721

- C.J. Rhodes, Solving the plastic problem: From cradle to grave, to reincarnation, Sci. Prog., 102(3)(2024) 218-248. https://doi.org/10.1177/0036850419867204

- N.S. Roslan, Y.Y. Lee, Y.S. Ibrahim, S.T. Anuar, K.M. Yusof, L.A. Lai, T. Brentnall, Detection of microplastics in human tissues and organs: A scoping review, J. Glob. Health, 14 (2024). https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.14.04179

- J. Sun, X. Dai, Q. Wang, M.C. Van Loosdrecht, B.J. Ni, Microplastics in wastewater treatment plants: Detection, occurrence and removal. Water Res., 152 (2019) 21-37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2018.12.050

- K.H.D. Tang, T. Hadibarata, Microplastics removal through water treatment plants: Its feasibility, efficiency, future prospects and enhancement by proper waste management. Enviro. Chall., (2021) 100264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envc.2021.100264